The first step in making feedback effective is to realise that it’s a two way street. Teachers, no matter how good they are, do not make learning happen. Equally, the most talented student won’t learn as much as they might without the instruction and guidance a teacher provides. Hattie and Timperley see feedback as a ‘consequence of performance’, but temper this definition with an important nuance: that feedback has its biggest effect ‘when addressing a faulty interpretation, not a total lack of understanding’. As teachers we therefore must understand what the students know before we can give useful guidance. Therefore a key role for a teacher is to ‘elicit evidence to promote discussion about learning’.

There is no simple answer to planning great feedback that will allow your students to thrive. It is as complex as they are. What I am about to outline is far from a complete set of ideas, but the following list may help you to focus on what you see as important for the lesson you are currently planning. The most important step is to develop a culture in which feedback is valued, wanted and well received. To do this we can consider:

- The routines, systems and procedures you use to ensure that ‘threat’ is reduced and feedback will not be interpreted as a personal affront

- The ways you can help students understand that feedback is part of the learning process

- The self and peer assessment strategies to develop student error detection and self-regulation

- How to value honest student responses so that errors are readily offered

What follows are some suggested planning questions and thought to ensure we get the right information from the students and then to consider how to provide the best feedback for student learning.

Six steps to planning receiving feedback from students.

Step 1 – Remind yourself of the long and short term learning intentions:

What was important last lesson?

What is important in this lesson?

What will be important next lesson?

What will be important at the end of the academic year?

Is this a threshold concept?

Step 2 – Where is the best place to focus the assessment?

Are you working on a long-term outcome that brings together many ideas and involves more complex thinking?

Are you working on short-term outcomes so repeating the information is key to longer-term learning?

What are the misconceptions, known difficulties and common errors associated with this concept or this task?

Step 3 – What exactly are you looking for?

How important is the idea? Is it a threshold concept? A known concept? A long term learning intention?

How might student knowledge change over time or over the teaching sequence?

How will you know if the students are getting to grips with this idea? How might this change as they become more confident or understand it better?

Are you looking to see if they understand the idea, if they know the idea or that they can apply the idea?

What might an exemplar response look or sound like?

Step 4 – Constructively align tasks and assessments:

Are you interested in the students developing or constructing meaning of the idea? Or assessing if the students have learned?

Is there any chance for ‘means end’ thinking or guesswork? Can they complete the task without thinking about the content?

Step 5 – Design assessments that you can trust:

Have I assessed the big idea more than once?

How big is the decision I will make based upon this information?

How much trust is necessary?

Do I trust that they know it? Or have they just worked it out from the clues in the assessment?

Step 6 – Make the information manageable:

When do I need this information? Can it wait for in between lessons to be processed and used?

Will sampling the class suffice?

Does having a valid assessment matter at this point in time?

How does the gathering of information fit with the flow of planned activities/ learning or the lesson?

Can a computer do the compilation of the evidence for me?

Eight steps to planning for giving feedback

Step 1 – Establishing the purpose of the feedback:

- Are students developing an understanding? Applying or building on knowledge? Producing work where quality matters? (Are domain skills involved)?

- Is there an opportunity to develop their self-regulation?

- Who or what is the feedback for? The student? To fulfil a policy? For observers?

Step 2 – Consider the form of feedback (or is Instruction needed?

- Do students know enough for the feedback to be helpful?

- Are the tasks constructively aligned enough for task level feedback to be helpful?

- Are answer sheets, guide sheets or rubrics needed?

- Will marking codes be a useful time saver?

Step 3 – Establish a context for feedback:

- How does the teaching sequence support the current learning?

- What prior knowledge do they need to be able to act on the feedback given?

- Are the learning intentions shared, agreed or owned by the students?

- How can you make the goals clear to the students?

- Is exemplar work used to set the direction and quality of the student work?

- Is a rubric established early in the sequence of producing the work?

- Is there a way of making the feedback something that is sought by the students rather than offered by the teacher?

Step 4 – Consider the timing of the feedback:

- Is the potential feedback needed for this task or concept best if provided immediately during the activity, or might some delay be beneficial?

- Is the task best defined as a construct, demonstrate or assessment task?

- How would testing and tests be structured in this topic to aid long term retention?

Step 5 – Establish the correctness, or not, of the student learning.

- What are the signs, evidence and clues that this piece of work is on the right track?

- Is there a hinge point opportunity?

- Is the hinge point activity robust enough to exposure misunderstandings and gaps in understanding?

Step 6 – Consider how the feedback will induce thinking:

- How does the feedback narrow down the range of potential answers or solutions?

- Does the feedback avoid leading the student to use a means end or a ‘trial and error’ approach?

- What are the purposes of your planned questions? Are they to assess, to induce thinking or a convoluted form of social control?

- Is there an opportunity for students to ask high quality questions?

Step 7 – Consider how the feedback develops self-regulation:

- Is student knowledge secure enough to add potentially extraneous cognitive load?

- What is the balance between securing knowledge and developing self-regulation?

- Is there a choice of meaningful tasks to follow formative assessment?

Step 8 – Set targets:

- What might you have to re-teach? How will you represent the ideas differently?

- What are the long-term goals for students with this concept?

- Is there any opportunity for ‘feed-forward’ between tasks?

- Do some targets take precedence over other? Or is some content currently more important than other content?

- Who is the target for: You? The whole or part of the class? Individuals?

Hand it out; show the kids what great work looks like.

Hand it out; show the kids what great work looks like.

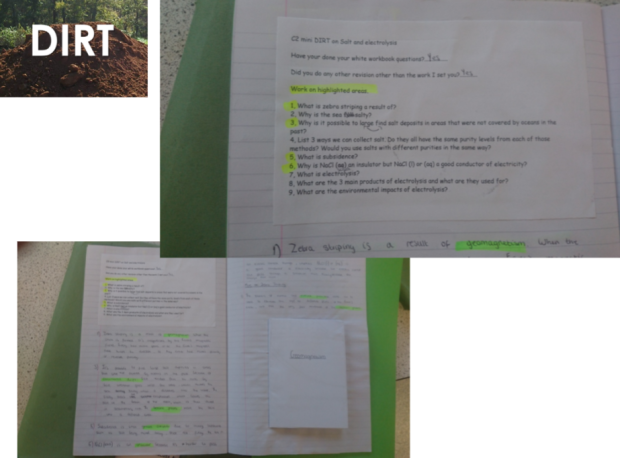

Concept check:

Concept check: